How to improve your note taking: the Zettelkasten Method

Organise your notes like a pro.

In either a well-reasoned and sensible move, or in a fit of naïve enthusiasm, I have very recently started a PhD.

With it, I thought I was long overdue audit on how I learn. I had gone through school, university and my masters with the same, ‘blunt object’ approach to reading:

Look through the papers, make pages (and pages) of notes on word, then spend hours pressing ‘Ctrl+F’ trying to locate the note that I would use in my essay.

Interspersed between the copied and pasted quotations and brief summaries, I would write down thoughts that occurred to me. Occasionally, I might highlight these reflections, or write them in bold.

By the time I had finished an essay, I had a mammoth document of notes. Now, this is great to make you feel like you’ve done a lot of work.

It is not so good when trying to find that useful piece of information you need for your literature review.

I had 90 pages of reading for my master’s dissertation.

With the start of my PhD — and the hours of reading and research I would be expected to do — I realised that this needed to change. I needed a more robust, effective method of organising my learning.

Flexible learning vs static

Learning is based on your brain making neural connections. Adding a component into your brain involves slotting it into these neural pathways. That way, new learning and ideas become embedded into the network of your consciousness.

The problem with organising notes in a notebook/word document is that they to often exist as separate entities. When you make a list of notes, it is very difficult to link an idea made on page 2 with another made in page 42.

This presents a big issue when trying to use these notes to learn.

Your brain does not exist like a notebook; different pages bound together in a rigid pattern. Your brain is fluid. It changes. New ideas connect to, and evolve, your previous understanding.

When thought of this way, it becomes apparent that rigid measures of note taking/learning do not complement the workings of your mind.

If the whole purpose of note taking is to relieve the pressure on your brain, shouldn’t those notes better reflect how your brain works?

Treat reading like preparing for an exam

The thing is, despite my reading and note taking, I was already aware of the power of more fluid — brain mimicking — approaches to learning.

At university, thanks to a fantastic tutor, I got into mind-maps.

I’m not talking about your run of the mill, simplistic mind-maps. No, I’m talking about your tree-like, colour coded works of art. This Medium article summarises quite nicely what I’m talking about.

Anyway, mind maps quickly became my ‘go-to’ way of revising. The way they allowed connections to be made between different ideas revolutionised the way that I prepared for exams.

Several years on, and I recommend them at every opportunity to the students I teach.

Despite advocating this fluid approach to revising, my approach to ongoing learning and note-taking is still stuck in the static dark ages.

It really shouldn’t be.

The thing is, essays and reports can be much broader than just preparing for an exam. Learning is ongoing. It doesn’t stop.

I can create a mind map to encompass a particular module. I would struggle to keep adding to one that encompassed my entire life and the everyday learning I make.

I don’t think it’s incredibly practical to reduce every note you take into a single mind map. It would get confusing and unwieldly pretty quickly.

There is a way, though.

In my research on how to read, and learn, more effectively, I stumbled across something that would change my approach to note taking.

The Zettelkasten Method.

What is the Zettelkasten Method?

German for ‘slip box‘, the Zettelkasten Method was based on the work of sociologist Niklas Luhman.

Without a hint of hyperbole, I think it’s fair to say that Luhman was a prodigious learner (and writer). Over the course of his life, he published 50 books and in excess of 600 articles.

Now, it is prudent to state — and I think self-evident — that Luhman was a workaholic. I am sure that his output, whatever method he used, would have been high.

That said, his inclination to work hard is not the sole reason for his prodigious writing legacy. For that, we have the Zettelkasten Method to thank.

How the overall system works

Simply put, the Zettelkasten Method utilises index cards. Ideas and thoughts are written on a slip of card.

You are most likely familiar with flash cards to illustrate concepts. You might have used them to revise ideas when at school.

Again, however, just like with pages of notes, flash cards exist in isolation from each other.

Imagine, though, you could connect these flash cards together.

That is the key, crucial feature of the Zettelkasten Method.

Luuhman would write his thoughts and reflections on these index cards. Each card, though, would be linked to another. No card would exist in isolation.

This transformed a relatively disparate method of writing notes into a powerful, brain-mimicking note-taking tool.

Tagging your Zettels

The original method used by Luhman used physical cards and storage boxes. More modern-day equivalents can utilise software to mimic this. My own Zettelkasten, for instance, is set up on Notion. Have a look here and here for the two templates I used as inspiration.

There are a whole host of ways that tagging can be used.

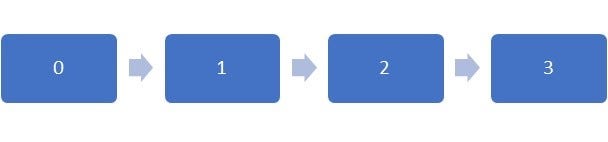

In the original method, Luhman numbered his cards (called ‘Zettel’s’) to illustrate how thoughts and ideas could be connected. An example of this tagging method is illustrated in the image below.

This, on its own, is hardly inspiring. The strength of indexing comes from the ‘nested’ indexing.

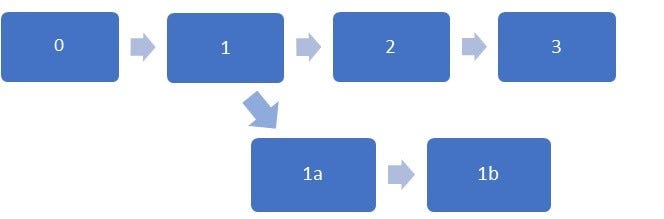

Say you read something, and develop a thought/idea, related to idea ‘1’. Rather than continue the sequence above and just index this Zettel as ‘4’, you would tag this card ‘1a’. This, therefore, creates a sub-branch, as illustrated below.

Anything stemming from Zettel 1a. would become 1b. and so on.

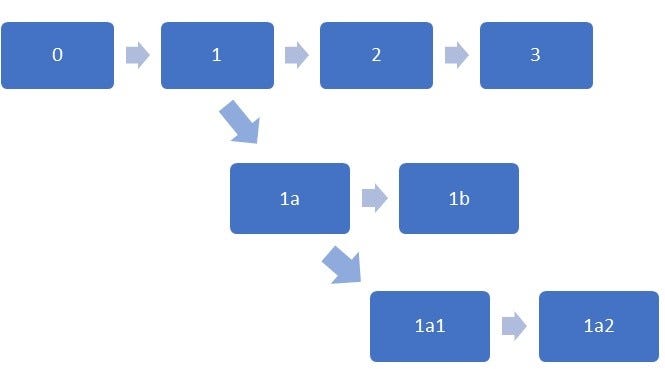

If we continue this theme, imagine I have an idea stemming from Zettel 1a., then I can insert the tab ‘1a1’ and so on.

At its simplest level, therefore, you can see how the Zettelkasten Method allows a more fluid mapping of knowledge.

Through creating these hierarchical tags, new ideas can be inserted into the framework of the Zettelkast. With the addition of every note you have to think about how best to integrate it within the framework of the other Zettels. You can map to see how your thinking has evolved.

In this way, the Zettlekast operates a little like a card-based mind map, where the different strands are kept on different cards but still linked to each different component.

The creative potential of a Zettelkasten. From croissants to…

If you want to fully visualise the benefits of Zettelkasten, I find it helps to liken the process of creating a Zettelkasten to Wikipedia.

Wikipedia, effectively, is structured in much the same way as a Zettelkasten. Pages in Wikipedia are ‘linked’ to each other, with headings and sub-headings used to differentiate between minor and major connections.

Type in a topic on Wikipedia — for this example, I have chosen ‘croissants’ (don’t ask why).

Start on this page, then click on a hyperlink within the entry on croissants to access another page. Now, continue to do this another 7 or 8 times.

By the time you have finished, you have likely arrived at a wildly different point to the one you started.

In the case of croissants, I ended up, on my 8th click, at the Sack of Constantinople in 1204.

Give it a try. Pick a start, choose the first link that catches your eye and repeat.

The learning is in the links

This jumping across pages in Wikipedia — Wikilinking (as it’s colloquially known) — is quite a fun pastime.

In the example above, I didn’t really pay attention to how croissants were linked to the Sack of Constantinople. Instead of just linking, though, say that I made a summary of how each stage of my linking connected together. Hypothetically, I could trace the links between croissants and the Sack of Constantinople and follow my thought process between these two, seemingly unconnected, ideas.

This is what a Zettelkasten does. It helps make links between ideas you could never have predicted making. It creates an organic, hyperlinked system of knowledge management.

As stated, learning is strengthened by making multiple connections between different concepts.

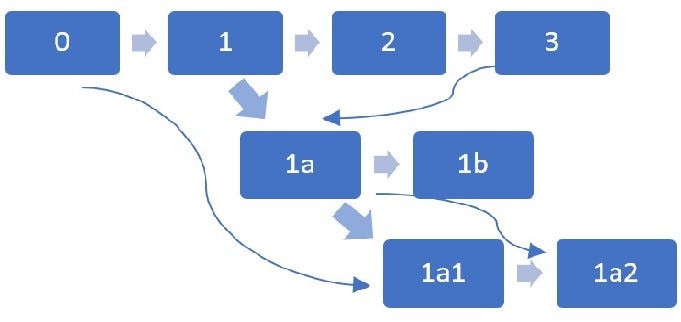

Once you get the hang of the indexing, you can start linking Zettels to other areas and ideas. Different notes can be cross-related to other areas of the Zettelkast, as shown in the diagram below.

In doing so, you can elevate the hierarchical structure of note management one step further. Now your notes become a web of connections between different areas of your thinking.

Connections can become more apparent. Your thinking and ideas become more creative and original.

What to include

Hopefully you have been sold on the potential of the Zettelkasten Method.

The question is, how do you go about creating your own?

Well, you need to read first. I would recommend making notes- much in the same way that you might usually do. This post is not intended to tell you how to make effective notes when reading.

You can find information out here though.

For summarising your reading/recording key takeaway points, this article has some great advice.

According to their introduction, every Zettel should include:

- A unique identifier. This could be a date/time stamp. I would also recommend adding a title for your card.

- Your piece of knowledge. It could be a thought, a conclusion, a reflection. Whatever it is, it needs to be written in your own words.

The crucial thing is that the Zettelkast should act as a summary of your reflection on the notes you have made from reading.

The way I look at it, producing a Zettel adds a crucial extra step that embeds your reading into the framework of your mind.

Make sure that you include links within your summary that link to other Zettels. This article has some great advice on how to do this.

3. At the end, include a reference where your reflection came from.

There we have it. Your notes and learning, revolutionised by the Zettelkasten Method.